How to shoot Super 8 film in 2020: A Digital Native’s Guide

If you’re like me, and you’ve spent the last decade of your life shooting on digital cameras, from 5Dmk2s all the way up to Sony Venices, shooting on film is probably something that you’ve always liked the idea of, but never really found the reason, nor the conviction, to see it through.

I mean it’s understandable — film is a seemingly expensive and sometimes cruel mistress. When you shoot digital, what you see is (for the most part) what you get, and you know that when you smash that record button, what you’ve recorded is pretty much what you intended to see. You also know that if it wasn’t right, or you changed your mind on how you’d like to shoot it, you can just keep smashing that record button until you’re happy or your re-usable cards run out.

When you shoot film, the second you smush your chubby appendage onto that shutter trigger, you’re literally spending money. If you’re not getting your exposure, focus or composition right, you may as well be shooting a big ol’ money gun into a furnace.

That being said, there is something inherently, inexplicably cool about shooting on film.

I won’t go on and on about it here, but there are definitely certain jobs that call for an analogue aesthetic. Now, I’m not recommending anyone who’s never shot on film before to go out and shoot their next project on 35mm, unless you’re really, really, REALLY confident in what you’re doing. I certainly wouldn’t even go near it without a knowledgeable crew around me. 8mm, on the other hand, is definitely conquerable, as long as you have a good enough understanding of cameras on the whole.

I recently went through this learning process while in pre-production for a short documentary, so I thought I’d distil the information for anyone who was interested in shooting 8mm. Buckle up.

Step 1: Choosing your Super 8 camera

Unless you want to chuff up big dollar bills and buy one of Kodak’s new “semi-digital” Super 8 cameras (Does that thing actually exist?) You’re going to need to find something used and ‘of the era’—the era being between 1965–1980…ish. This might sound a bit dodgy, buying something nearly 40 years old to use on a paid gig, but rest assured, the 1960s and 70s was a golden age of manufacturing. Just like your Mum’s Kenwood food processor, Super 8 cameras in the 60s and 70s were built like brick shithouses.

There are plenty of manufacturers to choose from. Some ol’ familiars such as Canon, and some not so familiars, like my personal favourite (for name reasons only), Elmo.

From speaking to several real humans and digging through some forums, it turned out that if you want something reliable, easy to use, and full of handy features, your best bet is either something made by Canon or Braun Nizo.

There are different models from each, ranging from entry-level up to professional. As far as I can tell, the main differences in models are akin to current cameras — if you get a premium model you get more camera speed (ASA) compatibility, more frame rate and shutter speed options, a better light meter, and a better lens. It seems that only the most spenny Super 8 cameras give the option of an interchangeable lens.

TOP PICKS FOR CANON: 814 XL-S, 1014 XL-S

TOP PICKS FOR BRAUN NIZO: 801, S80

After some deep diving on eBay, I concluded that the Braun Nizo 801 was a cost-effective purchase. There seemed to be more of them in a very good condition, and the price was very reasonable. There almost seems to be a cottage industry built on repairing and reselling them. We paid around £250 for ours, and oh boy, she is MINT. As with most technical purchases, you get what you pay for, and you really don’t want to cheap out on something like this.

Top tip: make sure whoever you’re buying it from has a good seller rating, and that they’ve mentioned testing it in the description. It just gives you a bit more security when it comes to knowing what to expect from the item, and having a leg to stand on if it shows up in several pieces.

The Braun Nizo 801

If you do decide to go down the Nizo route, here’s the low down. It runs on 6 x AA batteries, as well as 2 x 1.35V Weincell batteries for the light meter. It was crafted by Germans, so you know it’s solid. Wrapped in perfectly milled aluminium, it has a comforting weight to it.

When not in use, it has an articulating handle which tucks up behind itself, ensuring the batteries don’t get drained. The view-finder has an adjustable diopter so that you can adjust the image to your vision.

All of the buttons are obvious, intuitive and simple to operate. The camera comes with a Schneider 7–80mm 1.7 lens, which roughly equates to a 28–300mm lens in 35mm language (or 11x zoom). The lens has electronic operation for both its zoom and aperture functions, with manual options available, albeit still electronically controlled for the aperture. The light meter in the camera is directly linked to the aperture dial, and can automatically adjust to your environment by automatically detecting your film’s ASA speed.

It also has a geared reel counter, letting you know (approximately) how much film is left on your 50ft roll. You have the choice of three frame rates: 18 (for that classic film vibe), 24 (for that new-wave cine vibe) and 54 (for 3x slowdown on an 18fps timeline). There’s also the option for variable shutter speeds, mainly for shooting in low-light conditions.

The camera also has some peculiar settings, such as a “dissolve” and “fade to black” feature, which was maybe fun or useful before NLEs came along, but in 2020, it feels a bit novel.

Step 2: Choosing your film stock

Unlike 16mm or any other larger film formats, Super 8 is pretty damn easy to work with. No need to buy a tent or worry about having good enough proprioception to load in the dark. The film comes in a little cartridge that you simply plonk into the back or side of your camera and off you go.

If you’ve ever shot 35mm film stills, buying motion film stock won’t be a new experience for you, so you might want to skip the next section if you’re one of the lucky ones.

Different film stocks have different subjective, yet measurable, characteristics: contrast, saturation, colour rendition…the list goes on. The best way to get to know which stocks do what, and which ones you like, is to either test them for yourself or watch clips online. That’s a whole new adventure for you to embark on. From a purely technical standpoint, the most important things you need to look out for when buying film stock is the speed and colour temperature*

*you can also buy colour-reversal film, but don’t unless you’ve read up on it. I’m trying to keep this short, so I’ve chosen to omit it. If you want to know, ask! Otherwise, stick to negative.

Each film has an ASA rating, which in layman’s terms determines how sensitive the film is to light. If you’re used to digital cameras, ASA is equivalent to ISO.

The thing with film is that you can’t turn the gain up in-camera. ASA is fixed, and the way to brighten up your film if you’ve underexposed it is to ‘push’ it using a chemical process in the development. This introduces grain, which, depending on your desired outcome, could be a blessing or a disaster.

Generally speaking, if you’re shooting indoors, or in less well-lit conditions, opt for a film stock with an ASA of above 250. The caveat to shooting on a higher-speed stock is that the granulation of the grain itself is larger.

To draw a comparison to digital sensors: bigger pixels are more light-sensitive than small pixels. If you have bigger pixels, you get better low-light, but also lower resolution (hence the low-light power of the a7S). The same applies to film. If your exposure size is Super 8 and you use a lower ASA film, it’ll have smaller, more densely packed silver halides, which means that your film will be less sensitive to light but will produce sharper images.

Sometimes it’s better to just use more light and work with a lower ASA stock, sometimes it isn’t. It’s all personal preference, but good to learn, eh?

Alongside having a fixed ASA, film stock also has a fixed colour balance. It’s either tungsten balanced, or daylight balanced. That means that the film is produced to interpret either 3200k or 5600k as white. If you use daylight film in a tungsten room, it’ll look really warm and if you use tungsten film outdoors it’ll look really cold. There are times when this can be used for effect, but it’s good to at least know the rules before you break them.

You can also buy something called an 85 filter (some Super 8 cameras have this built-in) to offset tungsten film for use in daylight conditions, but this will cost you 2/3rds of a stop of light.

New vs. second-hand film stock

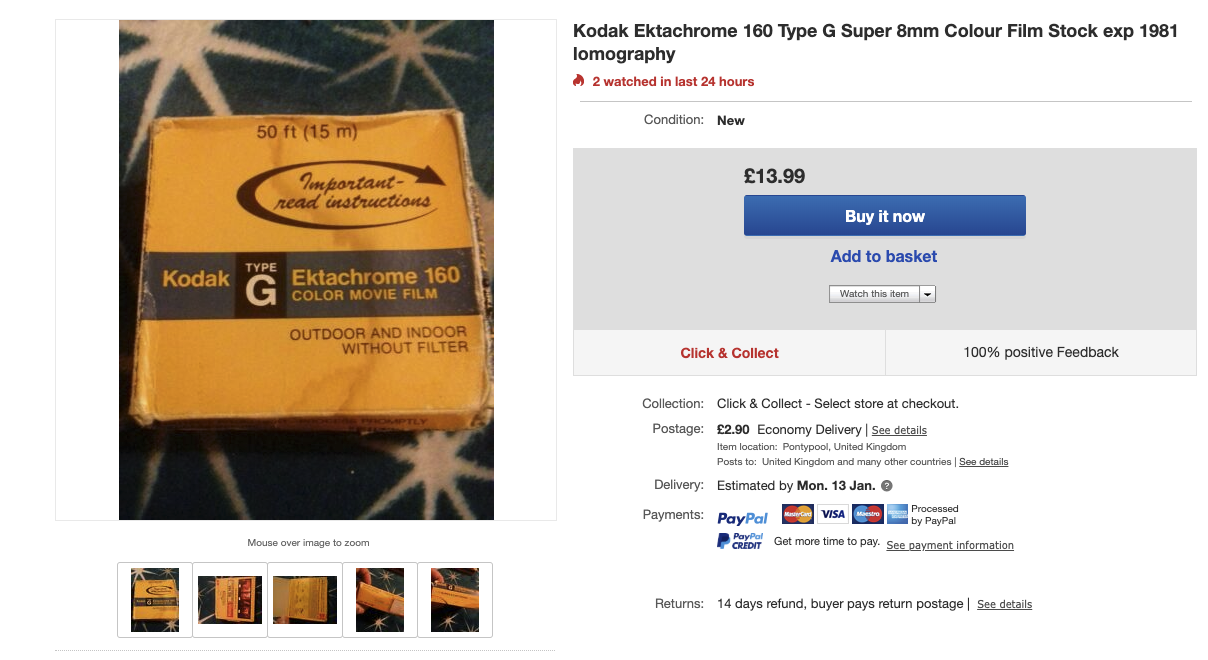

There are two ways of getting your grubby mitts on Super 8 film; you can either buy newly manufactured cartridges or adopt the more budget-friendly, if-not-potentially-risky approach of sourcing and purchasing old or expired cartridges.

The new stuff

At the time of writing, there aren’t too many companies manufacturing Super 8 film. The place that I purchase mine from (www.on8mil.com) sell two brands: Kahl and Kodak.

Kahl make quite a few flavours of film, none of which I have any experience in using, so try them at your own peril. Kodak, on the other hand, make only 5 stocks. They are their latest generation of stocks—the VISION3 stuff.

There’s plenty of resources online to compare them, and they perform as predicted every time, providing you store them well. They also produce the same VISION 3 stocks in 16mm and 35mm (and even IMAX), so you can shoot on the same stock as Hoyte Van Hoytema or Bob Richardson if you like. A film cartridge will cost you around £35, and, depending on your frame rate, will last around 2–3 minutes.

The old stuff

The risks associated with buying these are two-fold:

- You don’t definitively know how the film has been stored since purchase, which is a problem because humidity, pressure and temperature (not to mention magnetism and light exposure) all have an impact on the film itself.

- Each roll, even if it’s the same stock, will vary greatly depending on how it’s been kept. This means that if you wanted to shoot two rolls for a job, you can’t be certain that they’ll both come out the same.

If you are going to go down this route, there’s some good advice out there in terms of questions to ask the previous owner about how they’ve kept the film.

Martin Baumgartner, an industry rep and user of Cinematography.com, says the following:

Film that is to be used within 1 to 3 months can be stored at room temperature, but KODAK and other manufacturers recommend storage at 55F or less for film being stored 1 to 6 months. Longer than 6 months, it should be refridgerated, and longer than a year, it should be stored frozen. Get good quality ziplock freezer bags, evacuate as much air out of the bags as you can before you zip them up. Also, if you can do this in an environment at less than 60% Relative Humidity, that will help. The official recommendation is for ‘indate’ film, as with expired filmstock you need to store it cold so it will keep. So, for any ‘good useable’ expired filmstock, if using it within a year, refridgerate it, otherwise freeze it.

Shooting

So, you’ve got your camera, you’ve learnt how it works, and you’ve thrown a cartridge into the back of it. Off you go!

Do your best to calculate how much film you’ll need to shoot your project before you start, and stick to it. Ration it out accordingly. If you’re shooting a documentary, you’re likely to need a LOT more film than if you’re shooting a short film or lifestyle commercial.

All I can really say about shooting on Super 8, or any film, is that it isn’t limitless and it can’t be overwritten. Be frugal, and keep an eye on the reel counter. Similarly, try to keep an eye on your exposure. Overexposing film isn’t the worst thing in the world as most stocks will hold together even if overexposed by 3+ stops. If you underexpose, however—even by a stop—you’ve bought a one-way ticket to board the grain train and there ain’t no coming back.

Development and processing

First thing’s first, you need to get your spent cartridge out of the camera and post it off to a developer.

As I mentioned above, I use on8mil.com, who offer a variety of tiered pricing options dependent on turn-around speed and your development preferences. I’m fairly sure that they send it off to Germany to be chemically developed, and then do the digitisation themselves. Either way, they do a great job.

Push or pull?

When you send your film off, you can attach a note to the developer informing them of how you’d like your film treated. This works well if you’ve shot the whole reel purposefully under or overexposed by a stop, as they’ll be able to perform this correction chemically.

I don’t think this can be done on a shot-by-shot or scene-by-scene basis, so make sure you’re happy for your whole reel to be affected.

Resolution

Once your film’s been chemically developed, it has to be processed. This involves scanning the developed reel and digitising it.

There are more decisions to be made at this stage. First of all, you need to decide which resolution you’d like to have your film scanned at. Personally, I don’t think there’s much use in scanning Super 8 film above 2.6k, as each frame is only 8mm in size, so you don’t get too much additional benefit by having a 4k scan unless you plan on really punching in, which would increase the size of your grain. On8mil.com offer a 1.5, 2.6 and 4K scan of Super 8.

Frame Rate

If you shot at 18fps and you have your film scanned at 25fps, it will play back fast. If you shot at 50fps and have it scanned at 25fps, it will play back slow. If you match your scanned frame rate to the frame rate you shot at, it’ll playback in real time. The choice is yours.

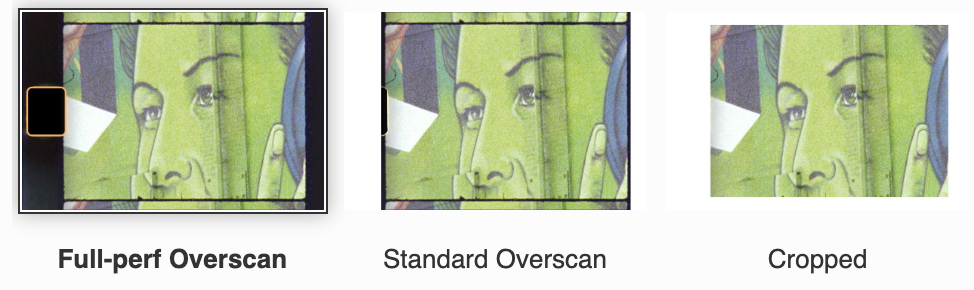

Overscan vs Underscan

This option is basically a “how hipster are you feeling?” slider.

Full-perf overscan scans the area outside of your exposed frames, allowing you to see the perforations as well as any other cool markings on the roll, like ‘Kodak’ which flashes up every now and then. That’s what I’d describe as “full hipster”. From there, you just choose what you want to lose, all the way down to a cropped scan, which is just the exposed frame itself.

Colour Correction

Lastly, you get the choice of whether or not you’d like the bloke at On8mil to give your film some colour correction and exposure correction before sending it back to you. This can be great if you’re a camera person but not a colourist, or if you’re really in a pinch, or just delivering the rushes.

The other option is to receive the scanned film in “log” or “light”. If you’re familiar with digital cameras, this is very similar to s-log or log-c. Very flat, very desaturated—putty in your hands. Mmm.

Editing

Once you’ve chosen your options and shelled out the appropriate fee, you’ll receive a download link to download your film as one or a few big files, usually in ProRes. All you need to do then is slap them into your NLE, chop them up as you would any other video clip, colour them accordingly and voila!

You’ve shot a project on film. Nailed it.

Conclusion

All in all, the total cost of purchasing a Super 8 camera doesn’t really substantiate a barrier to entry. After all, £200 is basically peanuts compared to the cost of a new digital camera, and certainly for one that can capture over 11 stops of dynamic range.

The real cost when shooting film materialises through peripherals. The cost of the stock, and of scanning and development. At its most premium, it can cost up to £160 ex VAT per roll, which is pretty steep for a hobbyist. If you’re being more financially cautious, it can cost as little as £50 per roll.

In 2020, where all data is overwriteable and you can buy a terabyte for £30, it’s easy to think that film isn’t cost-effective. In reality, I think if you cater your usage to your budget, you can produce some really brilliant results without it costing the earth, especially when you consider that you get the “film look” baked right in. Some people spend hours in the grade trying to replicate that look. I suppose you have to see it as more than merely buying data or buying card space. You’re buying into the century of research and development that Kodak and others have poured into perfecting their stocks.

I hope that this guide has given you the confidence, or at least the knowledge to think about giving Super 8 a go. Even though I pretty much omitted all emotion from the guide itself, shooting Super 8 is a hugely entertaining and rewarding experience, especially the first time you get your scans back and realise that you didn’t just throw £100 into a furnace.

Don’t forget to follow Storm & Shelter on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram for more delicious content!

Until next time,

LJ