How To Choose Your Glass

It’s true what they say, no one lens can do it all. It doesn’t matter how fast it is, how much zoom it has or how sharp it is.

Think of it this way. Imagine you have a really good chilli con carne recipe. You love spicy food, and God-damn, this chilli is forged with hell-fire, using only the most stomach-incinerating, tongue-torching Carolina Reaper chilies. To you, it tastes great, full of strong flavours, a great go-to on a Thursday evening.

But imagine what would happen if, when told you have to prepare a meal for a your niece’s 7th birthday party, you decided to go with said Chilli. High pitched screams rattle the dining room as one by one the once excited, hungry children fall victim to a Tex-Mex roasting. What started with perfectly honest intention has resulted in having to make an emergency trip to the supermarket to fetch 3 gallons of milk and a bumper pack of toilet paper to deal with the aftermath. You’ll not be invited back next year.

Although this example may be a touch hyperbolic, the sentiment is very much relevant. Choosing the appropriate (I say appropriate to avoid using the term ‘correct’, as in my opinion there is no correct lens for any job, it’s all subjective, yo) lens for each job can go a long way to determining the success of a shoot before you even set foot on set.

You might be thinking “Bloody hell Jelley, get off your high horse. I bet you’ve made at least one mistake in your whole stupid life”. You’d be correct, except I’ve made several.

The most poignant case I remember is back when I first started shooting with my 5Dmk2 in 2012 (roughly) and I was asked to produce a Kickstarter video for a tech related startup based in a robotics lab. I’d very recently purchased a vintage Helios 58mm and was besotted with it. It was indeed a very interesting lens; lovely diffusion, flaring and overall filmic texture. It was also rather soft, not contrasty in the slightest and to be honest not very sharp, which gave me quite a big kick in the dick when it came to matching the shots I’d taken with it with those that I’d shot with some of the Canon L series lenses that I’d also taken with me.

Not only did it not match the other lenses, but it also didn’t in any way represent the feel of the company’s brand or product, which was based very much around vibrant colours and technical details. Luckily, I was able to work around these shots, but I’d learnt a valuable lesson, one which I’m going to try and explain now.

If you’ve read any of my other blog posts, then you’ll know that I’m a big fan of anamorphic and vintage glass, however I completely accept that they’re not right for every job.

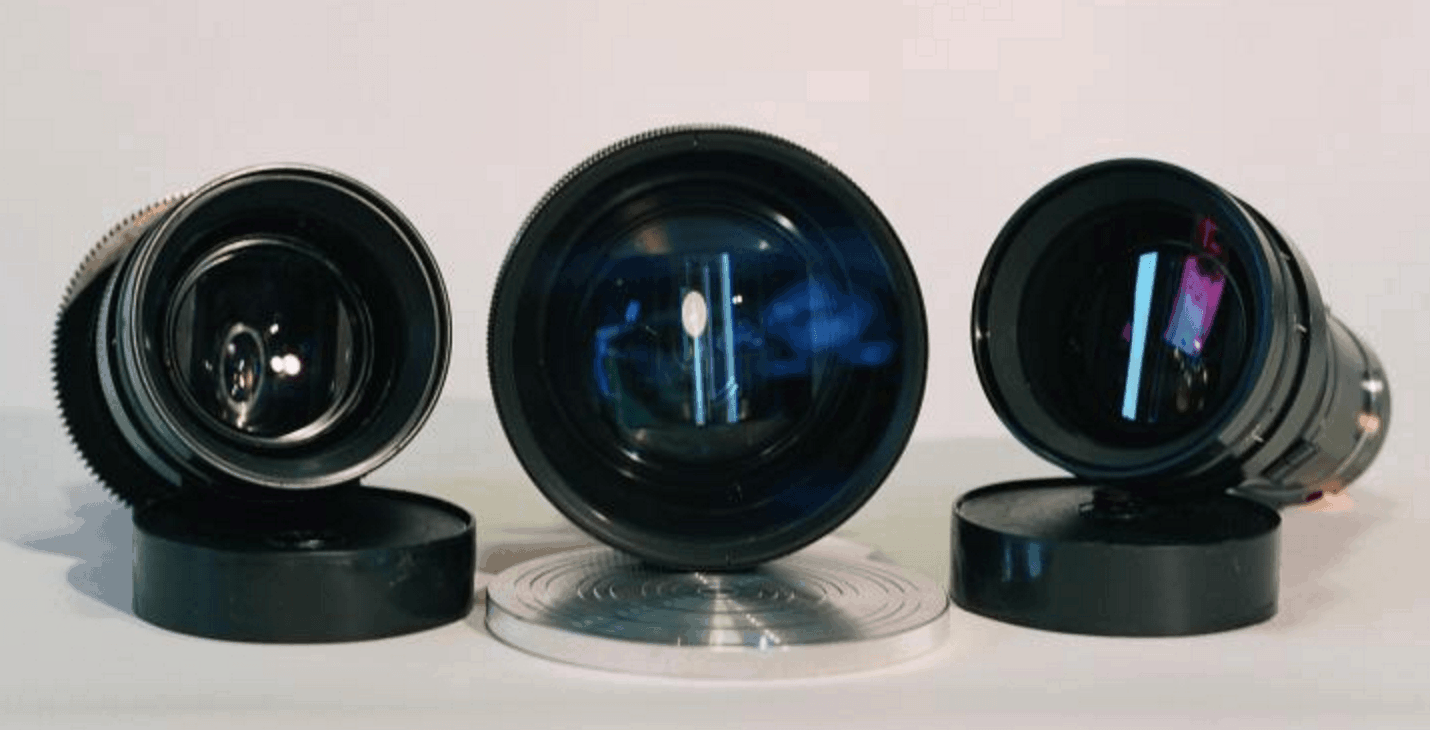

Lens coating (and flaring), texture, sharpness, colour, diffusion, bokeh, contrast, vignetting, how the focus breathes, anamorphic vs spherical and imperfections (wanted and unwanted) are all characteristics to consider when choosing a set of lenses. To help you determine what characteristics you might want for your next project, here are some key questions to ask yourself:

What is the Director’s vision for the story?

This should (most of the time) be your starting point as a DoP when it comes to discussing lens choices. How does your director visualise his film? What are its characteristics? What is the story really about, and what emotions and relationships does it portray? Think about how certain stories and characters have traits that can be emphasised and enhanced by lens characteristics. At the end of the day, your role as DoP is to help realise the director’s vision.

What time period is the project set in?

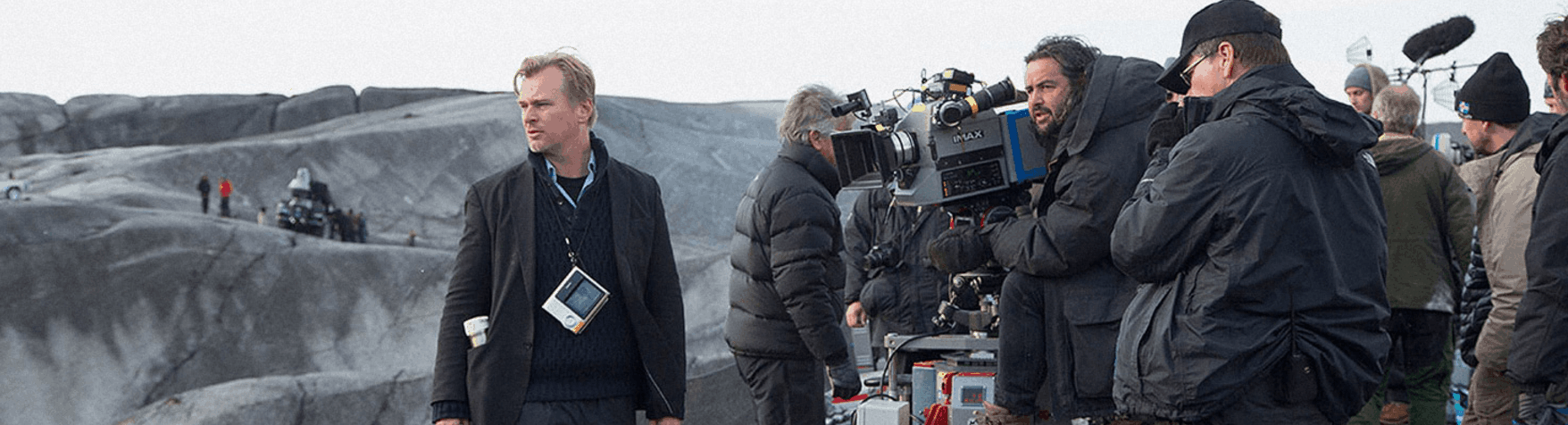

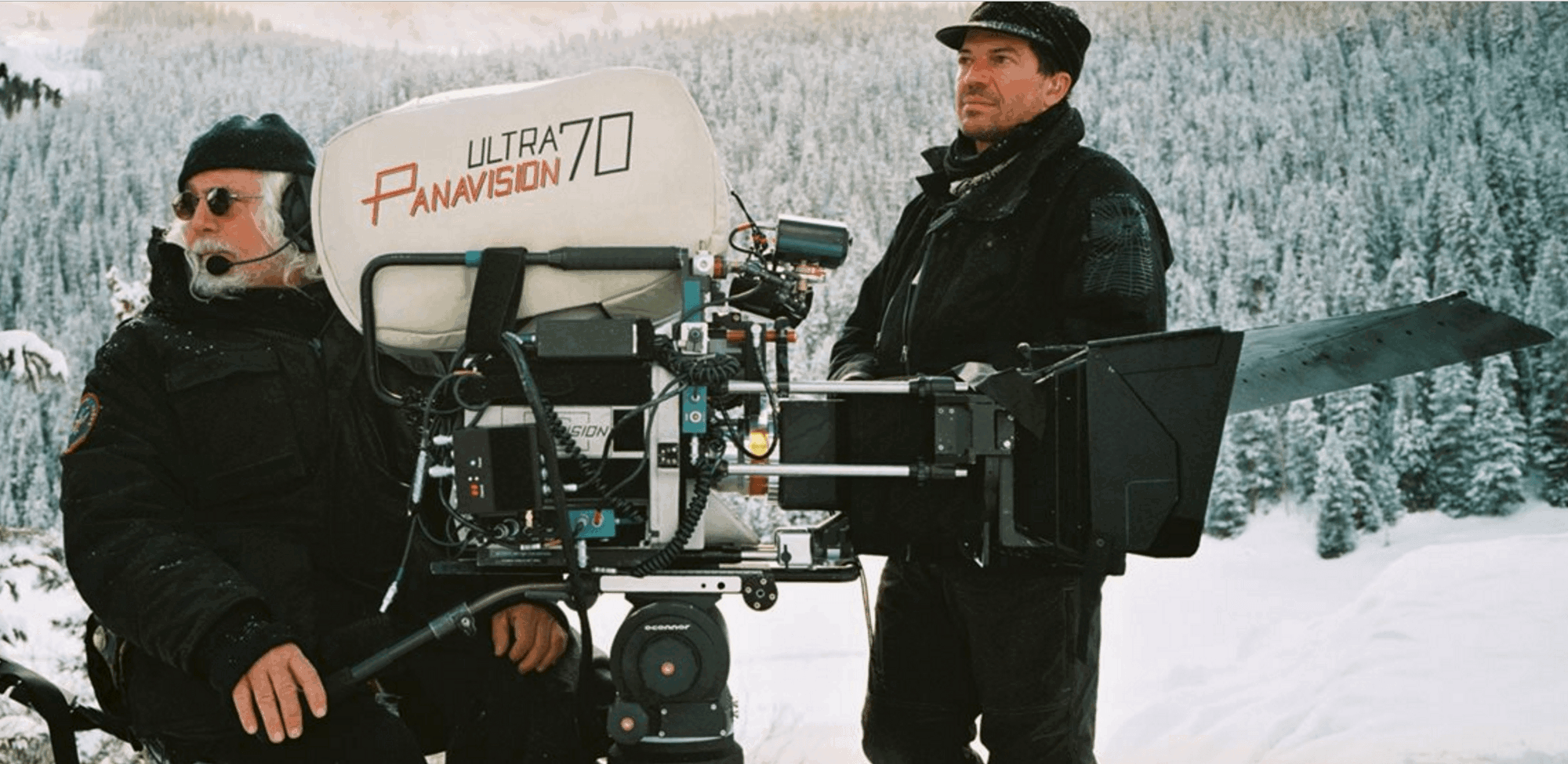

This is one of the more literal and denotative examples of choosing a lens. If your project/film is set in the 60’s, it’s more likely that you’ll want to recreate the classic “film” look, in which case vintage, spherical or anamorphic lenses might be the best choice. A great example of this is Tarantino’s Hateful Eight, where they decided to shoot with really old 70mm Panavision lenses to give the audience a really authentic, classic movie experience. Modern day and sci-fi films tend to lean towards sharper, more clinical modern spherical lenses, to give the film a more technical, precise vibe. There are exceptions to this, as I’ll mention below, but it gives you good food for thought.

What is the main subject of your film?

When I say subject, I mean “whatever is going to spend the most time on screen” during your project. If you are shooting a dialogue-heavy movie that features people heavily, you’re going to want a set of lenses that can reproduce skin tones well and emphasise facial shapes and tones. If you are shooting a car commercial or product, you need to think about what works best to bring out the detailing of the object.

Shane Hurlburt does a great lens shootout between Cooke S4/i’s and Leica Summicron’s which gives you a good idea of what I’m talking about:

What is the tone of your film?

Shooting a romantic period drama is obviously quite different to shooting a post-apocalyptic thriller. Your lens choices should be reflected in this. What are the main emotions? If they’re love, happiness and caring, you probably want to look for something that diffuses light well and has less contrast and creates warm tones. If they’re horror, panic and evil, perhaps something sharper with more contrast might be appropriate.

Which camera are you shooting with?

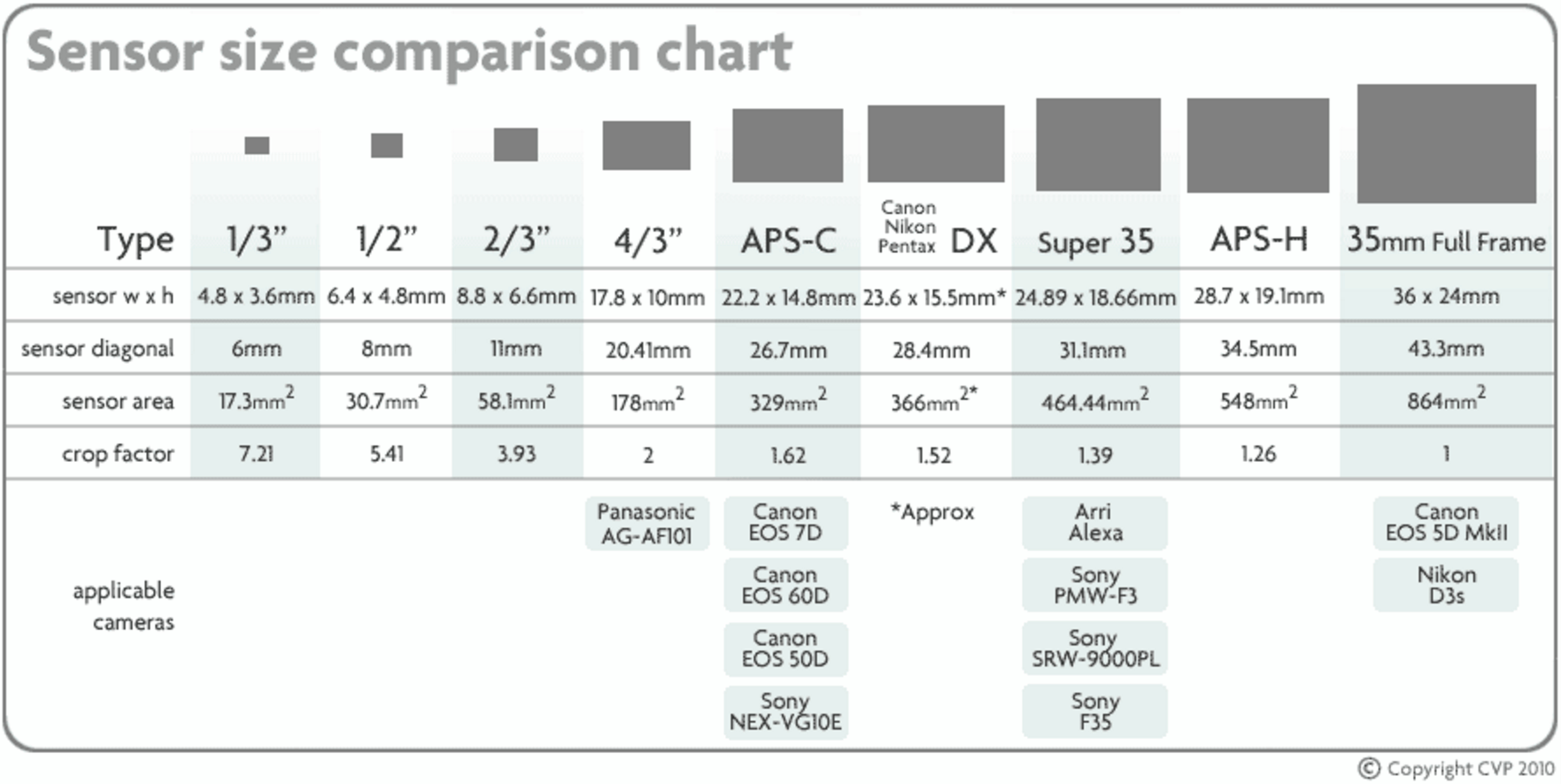

This is more of a technical consideration point than anything else, but you still definitely need to give it some thought. If you’re shooting with 2x anamorphic lenses, does your camera have a 4:3 sensor crop option? Or are you happy with a 3.55:1 aspect ratio? (which is fine, I’ve done it!). Can the lenses you are using cover the whole area of your sensor? If you’re shooting in 65mm format or using a RED, you probably need to check, as there are only a certain amount of lenses that can cover a sensor so large.

What are your shooting conditions likely to be?

Again, more of a technical one. As I recently learnt, vintage anamorphic lenses are some of the heaviest primes in the business. Shoulder mounting them for an 8 hour day was a pretty savage task. Unless you have the upper body strength of Hoyte Van Hoytema, you should probably take the shoot style into consideration. If you are going to be shooting a moving target or a run and gun style documentary, you probably want to choose a zoom lens in order to be versatile enough to get the shots you need without changing lenses all the time. Temperature and weather is also important, as some lenses are more weather-sealed than others, and some are far more prone to locking up in cold conditions (again, something I’ve discovered first hand).

How much budget do you have?

Very obvious, this, but you probably shouldn’t be telling your producer that you want to shoot on Cooke anamorphics if you only have £200 a day set aside for lens rental. That’ll probably just make him internalise some hatred for you that will manifest itself later on that evening when he doesn’t get ketchup with his McDonald’s meal and burns the place to the ground.

Anyway, there are usually always other options to explore to get the desired effect, and it’s good to have a solid list of lenses to explore for different types of budgets. It’s also worthwhile to mention that although a lot of the time you get what you pay for when it comes to lenses, you shouldn’t just go for the biggest price tag you can afford. Blind tests are great for this as they let you make an unbiased decision without any pretence surrounding manufacturers or reputation.

Exceptions

After reading the above, you might think:

“Christ, Jelley, you’ve pinned me in here. If these are the rules, how am I supposed to be creative?”

Firstly, I am just one man, you can ignore me if you like. I’m not your Dad. Secondly, rules are made to be broken and in a lot of instances should be.

One of my favourite examples of this is the recent Star Trek franchise, whereby my main man JJ Abrams cast aside the boring, sterile look of sci-fi movies that preceded it (*cough* Star Wars 1–3) and decided to introduce a boat-load of flares to give the film a more personable touch. He may have gone a bit overboard, but fuck, you can’t blame a guy for trying something new.

As much as lenses can be used to compliment the story, they can also be used to create a juxtaposition and contradiction. Zak Snyder, a man who seems to have run out of shits to give about maintaining stereotypes, used high contrast Panavision Primo lenses when creating the film 300, a film based on something that happened thousands of years ago. As long as you aid the Director’s vision and stay true to the story, you’re golden.

Resources

As I am well aware, testing lenses is a luxury for many. The time alone involved in doing this is a put off to some, while the cost of renting lenses to test may seem unnecessary and expensive.

From my own experience, I’d always air on the side of testing lenses before you shoot with them if you possibly can and the budget allows. Not only does it give you and the director a chance to make an informed decision, it gives you an idea of what the lenses will actually be like to work with.

If this isn’t possible for whatever reason, there are a fair few places that I consider to be my go-to when trying to look for reasons to shoot with certain lenses. Check out the below links for some tasty resources:

I hope this at least goes some of the way to helping you understand why lens choices are so important. If nothing else you now know about the dangers of cooking spicy food for a children’s birthday party, and if I’ve achieved that, I can go to bed happy.

Ooh, it’s Monday — chilli tonight!

Until next time,

LJ